The first time I met Beverley was when we were both helping at a conference that was organised by postgraduates for prospective research students at the University of Aberdeen in 2012 – the PhD Journey Conference, which was masterminded by Catherine MacDonald, a fellow PhD student. Thereafter, we kept loosely in touch via LinkedIn and finally met up one fine afternoon in the summer of 2016. That’s when we had that fateful conversation, which led me to rethink the purpose of Blue Steens.

Let’s have a chat with Bev …

Bev, tell me a bit about your scientific background.

I completed a BSc in Applied Biosciences and Chemistry because I have always been interested in the interaction between biology and chemistry. Interestingly, I have been told that it is quite rare to find a biologist with profound chemistry knowledge and skills.

I went on to gain a Postgraduate Diploma in Instrumental Analytical Sciences during which I performed biochemical tests on various biological materials and analysed cell function. After few months of voluntary work at the James Hutton Institute in Aberdeen performing soil analysis and a stint at the Marine Laboratory as Analytical Chemist, I decided that I wanted to work in hospitals. So, I completed an accredited MSc in Biomedical Sciences at Kingston University, and worked as a Biomedical Scientist with the NHS Grampian in the microbiology department of the hospital and later for a private company.

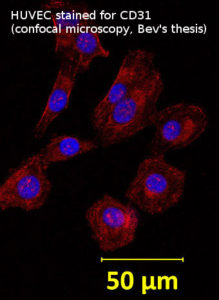

Eventually, I wanted to develop further and get more into molecular biology. So, I accepted a post as a PhD student in Immunobiology at the University of Aberdeen in 2008. The project had a strong biochemical and molecular focus by studying inflammatory cell responses to antioxidants.

Since my graduation in 2014 I have worked in different positions. I did proof-of-concept method development for an NHS project at the University of Aberdeen. Then I joined the immunohematology research group to study the effects of reactive oxygen species on red blood cells. I’ve been involved in this project since autumn 2014. Meanwhile, I have also worked as Locum Biomedical Scientist for the NHS for half a year in London.

You seem to be working in a lot of short-term arrangements. Could you imagine creating a sustainable life-style as a freelancing biomedical scientist?

That would be tough, at least with the systems that are currently in place. As you indicate, I have done this for a good few years now, and I know people who prefer locum positions. It would certainly be interesting and keep your skills up. It would also add an element of freedom to your work life. I have met some scientists who work for 7 months or so and take the rest of the year off!

I think it would be feasible if enough jobs were available locally so that travel and accommodation won’t cost you too much. You’d also need enough money to cover other expenses that an employee gets with a benefits package like pension savings or sick pay. In the end, you need a constant income to make a living.

When we met few months ago, you actually came up with the idea of a freelancing scientist. This is a big part of the reason I looked into creating an online marketplace for short-term scientific projects. How has your idea come about?

Basically from volunteering my scientific knowledge and skills. Every so often a fellow researcher would ask me a question in my fields of expertise and sometimes a project would arise from this. After having worked in several different projects like that, I started wondering whether I could create a reliable income stream out of this by landing regular short-term assignments. In principle, I imagined a sort of lab-based scientific consultant role as opposed to an office-based consultancy. It also helped that my partner kept prodding me to charge people for my contributions!

Do you think it would be difficult to adapt to the varying demands of different projects?

No. In science you need to be adaptable anyway. Especially in a research environment the demands of a project change all the time, and you need to adapt to these. I have such a broad background now that I can basically go anywhere and do anything within my areas of expertise. Of course, there will always be an element of initial training or the need for an induction to the specific requirements of each new project, but this is generally a very short period. A good scientist with years of experience should pick new things up quickly.

From a freelancer’s perspective, do you have any advice for companies on how to make the running of short-term projects smooth and efficient for both sides?

An absolute must to allow for a speedy start is that the company has clear and accurate SOPs or lab protocols in place. After reading these, I should be able to perform a few test runs, which are validated against existing data. Once that is OK, I would be good to go unsupervised.

Companies should also make sure they employ a freelancer who already has the skills they need because, obviously, this shortens the induction time drastically. They should also be very clear and honest about their expectations. For example, it should be stated if the job is very fast-paced or repetitive, as not everybody is used to such demands. A freelancer who hasn’t experienced many different working environments might be surprised or adapt slower to unfamiliar requirements.

Companies also need to be realistic about the time requirements. If there is a project that only requires me to run loads of routine tests, the induction phase will be short. But if it involved data interpretation, it really depends on its complexity and novelty how fast a freelancer can pick things up. If a company wants this done right first time, they need to budget in sufficient time for training to avoid frustration on both sides.

Thanks for sharing your insights, Bev.

Interview conducted by Dr Christiane Wirrig

Deutsche Version auf der nächsten Seite.